Hi there,

“Don’t focus on retention.”

A client recently told me they received advice that retention only matters later, that they should focus on acquisition first.

Yeah… that advice definitely didn’t come from me. But they’re not the only ones who’ve heard this so-called wisdom—it’s way too common.

I get why. When you’re looking at monthly revenue, acquisition seems like the big winner. But here’s the real math behind why retention actually matters now—and how to know if it should be your focus.

The Scenario

Imagine two possible scenarios for a product typically ordered once a month. Over the next year, we focus on one of the following:

Reducing churn by 15%

Reducing CAC by 15%

Of course, this is a simplified view—it doesn’t factor in other costs or the reality that acquisition costs often rise. But it gives a general idea of the impact.

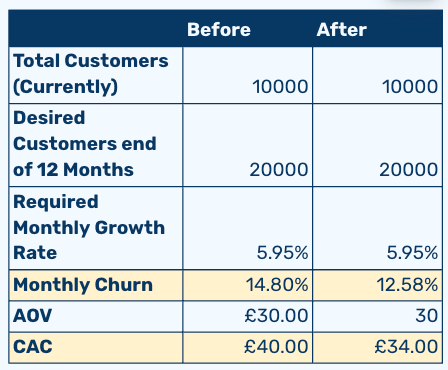

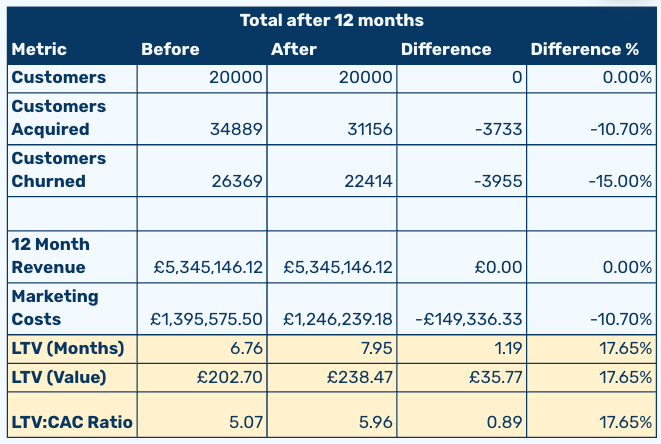

In the table below, ‘Before’ represents the current situation, and ‘After’ shows what happens if both churn and CAC decrease by 15%:

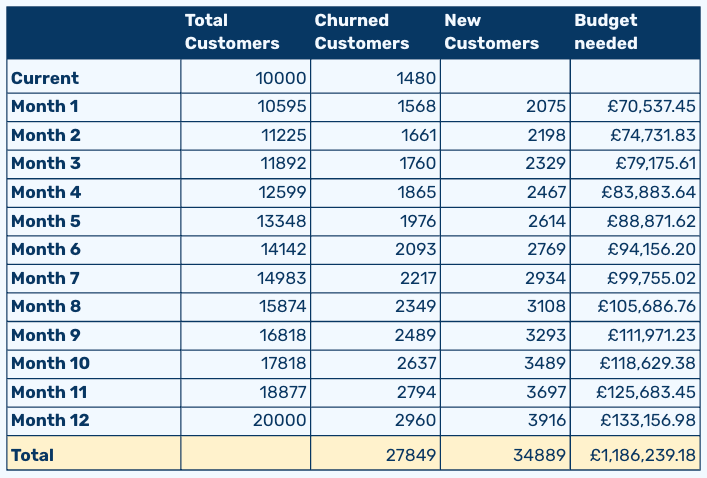

Our baseline scenario looks like this: With a 14.80% churn rate by year-end, we needed 34,889 new customers to grow from 10,000 to 20,000, because 27,849 customers churned along the way.

It cost us £1,395,575.50 to acquire those new customers—ouch.

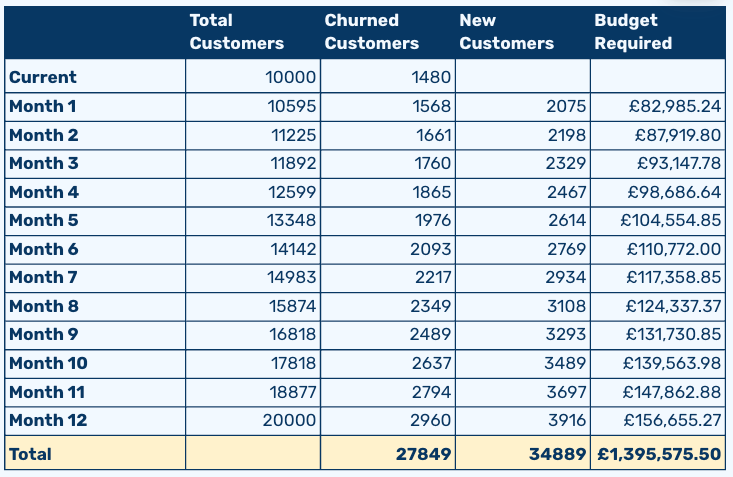

Scenario 1: What happens if we reduce churn by 15%?

With 12.58% of customers churned by the end of the year, we needed 3,733 fewer new customers and have saved £149,336.33 on marketing spend to achieve the same growth—great!

Not only have we reduced the number of new customers needed and lowered marketing costs, but we’ve also increased lifetime value and average customer duration by 17.65%.

This means higher profitability and a healthier business—plus, we’re in a better position to keep scaling even if CAC rises. Given that a healthy LTV:CAC ratio for this organisation is 5.5:1, our maximum CAC here is £43.36.

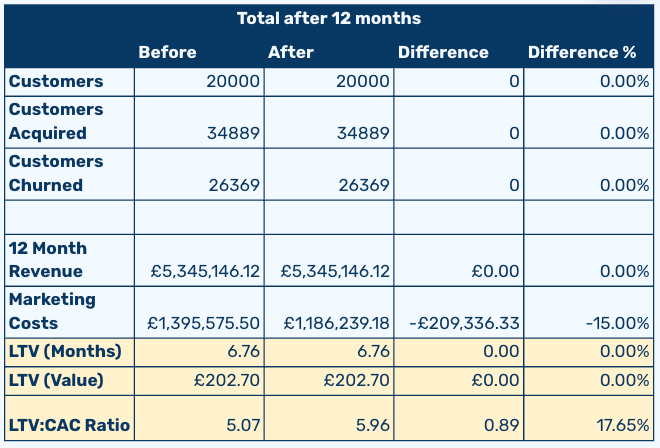

Let’s run the same scenario with reducing CAC.

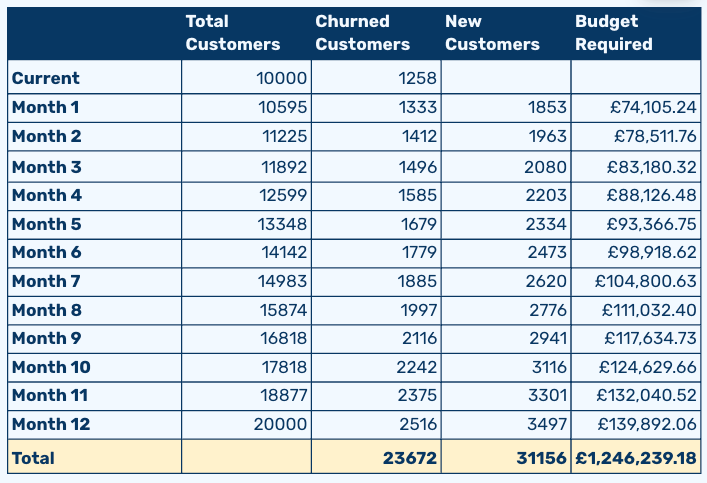

Scenario 2: Reduce CAC by 15%

The same reduction in CAC seems to save more with a £209,336.33 reduction in costs... but we still need to acquire 34,889 customers.

In this scenario, we still need to acquire the same number of customers. Yes, the LTV:CAC ratio improves, but our actual LTV doesn’t increase, which means we’re still capped on how much we can spend to acquire customers.

Since we established that a healthy ratio for this organization is 5.5:1, our max CAC is now £36.85—15% lower than the previous scenario. Why? Because LTV is lower, limiting how much we can afford to spend on acquisition.

Other impacts of Scenario 1 vs Scenario 2

There are even more reasons beyond just a lower CAC that make Scenario 1 superior to Scenario 2:

Every customer comes with costs—customer care, tooling, onboarding, etc.—and these costs are higher in Scenario 2

Scaling acquisition requires more people and marketing efforts, and CAC usually increases with higher acquisition, not decreases

As a result, profitability is likely lower in Scenario 2

You’re forced to work with a lower CAC. In this example, we assumed a growth goal, but if you can justify a higher CAC, your ceiling is much higher

Customers who stick around longer are more likely to refer others, creating organic growth over time

So this year, instead of endlessly chasing a lower CAC, think about how focusing on retention and improving LTV can make growth easier. CACs are only going up, making acquisition a tougher game to win.

Not sure where to start, here would be my steps:

Work out where we are losing customers, e.g. 1st to 2nd order, 3rd to 4th order, after a year, etc.

Based on that work out a relevant cohort of customers to interview and speak with, e.g. if it’s 1st to 2nd order I’d speak to customer who have and haven’t ordered a second time that match the ideal customer.

Create a clear plan of improvements around that metric, ensuring you aren’t looking just at this quarter’s results but longer-term (as retention takes longer to improve).

Recommendation

In every edition of Growth Waves, I also share a related resource to check out related to the week's topic.

You know that book that just about everyone seems to recommend? So you finally read it, assuming it can’t be as good as people claim. Well, for me, this is Oversubscribed by Daniel Priestley. You may have seen it in my recent newsletter on my next five reads.

So feel free to act as my virtual book club and read along with me. It only feels right to recommend a book about getting people to line up and stay in today’s crowded markets.

If you’re wondering where all these numbers came from—fun fact: I have a Master’s in Finance & Investments.

But I quickly realised that most of my peers were aiming for banking careers, and while I love numbers (and a good Google Sheet), the work 80 hours to get rich mentality wasn’t for me. I’d rather help the little guys grow.

Luckily, those skills still come in handy now and then!

Till next week,

Daphne